More Information

Submitted: July 11, 2025 | Approved: July 15, 2025 | Published: July 16, 2025

How to cite this article: Sayed Z, Bellot V, Gorikapudi K. An Unexpected Alliance: Coexisting Alport Syndrome and IgA Nephropathy in the Setting of Socioeconomic Barriers. J Clini Nephrol. 2025; 9(7): 087-089. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jcn.1001162

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jcn.1001162

Copyright license: © 2025 Sayed Z, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy; Alport syndrome; Thin basement membrane; Hematuria; Proteinuria; Genetic testing; Health disparities

An Unexpected Alliance: Coexisting Alport Syndrome and IgA Nephropathy in the Setting of Socioeconomic Barriers

Zaheeruddin Sayed1*, Victoria Bellot1 and Kundan Gorikapudi2

192-29 Queens Blvd, Suite 2A, Rego Park, NY 11374, USA

2Kamineni Academy of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Hyderabad, India

*Address for Correspondence: Zaheeruddin Sayed, 92-29 Queens Blvd, Suite 2A, Rego Park, NY 11374, USA, Email: [email protected]

Background: Alport syndrome and IgA nephropathy (IgAN) are distinct glomerular diseases that may present with overlapping symptoms, including hematuria and proteinuria. Their coexistence is rare and can complicate diagnosis, primarily when socioeconomic barriers to care exist.

Case report: A 50-year-old Nepali male with persistent proteinuria and microscopic hematuria was found to have coexisting IgAN and autosomal dominant Alport syndrome, confirmed through renal biopsy and genetic testing. Management was limited by financial constraints that prevented access to advanced therapies. Urological evaluation showed congestive hemorrhagic cystitis secondary to benign prostatic enlargement contributing to hematuria.

Conclusion: This case highlights the diagnostic complexity and management challenges associated with dual nephropathies, underscoring the importance of genetic testing and socioeconomic factors in the delivery of care.

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common primary glomerulonephritis worldwide, typically presenting with hematuria and proteinuria [1]. Alport syndrome, a hereditary nephropathy caused by mutations in type IV collagen genes, is most commonly X-linked, but autosomal dominant forms involving COL4A3 or COL4A4 mutations also exist [2,3]. The coexistence of IgAN and Alport syndrome is rare and may complicate diagnosis, especially when classical histologic features of Alport syndrome are absent [1,4]—socioeconomic barriers, including lack of access to advanced therapies, further challenge management [5,6].

A 50-year-old male of Nepali origin, with a medical history significant for hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and stage 3B chronic kidney disease (CKD), presented for evaluation of persistent proteinuria and microscopic hematuria.

During his evaluation for CKD, routine laboratory testing revealed a markedly elevated urine albumin/creatinine ratio of 4600 mg/g. His glycemic control was suboptimal, with an HbA1c of 7.5%. Serum creatinine levels fluctuated between 1.42 and 2.1 mg/dL, with corresponding eGFR values ranging from 30 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m². Despite these findings, the etiology of his proteinuria remained unclear following initial assessment. Given the degree of proteinuria in the context of diabetes, a renal biopsy was pursued to further clarify the underlying pathology.

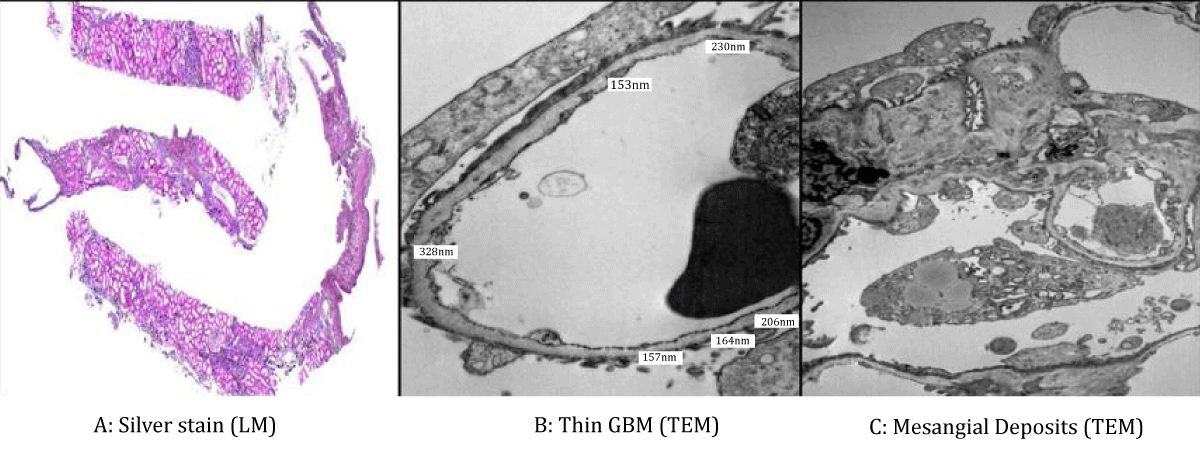

Light microscopy demonstrated glomeruli with mesangial expansion, areas of segmental and global glomerulosclerosis, and moderate interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy involving approximately 30% of the cortical tissue. These findings corresponded to an Oxford classification of M1 E0 S1 T1 C0. Immunofluorescence staining revealed granular mesangial deposits of IgA (1–2+), IgM (2+), and lambda light chains (1–2+), with no significant staining for other immunoglobulins or complement components. Electron microscopy showed thin glomerular basement membranes, with a mean thickness of 217 nm (range 153 - 328 nm), without evidence of lamellation or splitting of the lamina densa. Frequent small mesangial electron-dense deposits were identified, along with segmental podocyte foot process effacement (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Light microscopy (silver stain, low magnification) showing mesangial expansion, segmental sclerosis, and moderate glomerulosclerosis (Figure 1A). Transmission electron microscopy demonstrating diffusely thin glomerular basement membranes (mean 217 nm; range 153–328 nm) without lamellation or splitting. While not diagnostic on its own, these findings suggest thin basement membrane disease and correlate with a genetically confirmed COL4A3 mutation consistent with autosomal dominant Alport syndrome (Figure 1B). Transmission electron microscopy reveals small mesangial electron-dense deposits and segmental podocyte foot process effacement, consistent with IgA nephropathy (Figure 1C).

Given the severity of proteinuria and the inconclusive nature of histologic findings, genetic testing was performed using the Renasight panel. This revealed a pathogenic heterozygous variant in COL4A3, consistent with autosomal dominant Alport syndrome, as well as a likely pathogenic heterozygous variant in COL4A4. The heterozygous nature of these mutations likely accounted for the absence of classic ultrastructural features of Alport syndrome on electron microscopy and the relatively mild extrarenal manifestations.

The patient was additionally referred for urologic evaluation due to persistent hematuria with normal red blood cell morphology. Cystoscopy identified moderate prostatic enlargement, causing bladder neck obstruction and features of congestive hemorrhagic cystitis. No bladder tumors or calculi were detected, and mild fulguration of the bladder wall was performed to control bleeding.

Ophthalmologic examination was conducted to assess for diabetic retinopathy and Alport-related ocular abnormalities. No features typical of Alport syndrome, such as anterior lenticonus or retinal flecks, were observed. The examination revealed myelinated nerve fibers in the left optic disc, bilateral regular astigmatism (corrected to 20/20 vision), and bilateral dry eyes.

Financial constraints complicated management of the patient’s dual nephropathy. Advanced therapies, such as Tarpeyo and Filspari, were considered but deemed infeasible due to high insurance deductibles, and the patient declined to incur out-of-pocket costs. Instead, he was provided with samples of empagliflozin (Jardiance) and finerenone (Kerendia), and efforts were initiated to assist him in enrolling in patient assistance programs to support future access to necessary medications.

Coexistence of IgA nephropathy and Alport syndrome is rare and presents unique diagnostic challenges. While IgAN is the most prevalent primary glomerulonephritis worldwide, Alport syndrome is a hereditary disease resulting from mutations in type IV collagen genes, predominantly COL4A5 in X-linked disease, but also COL4A3 and COL4A4 in autosomal dominant or recessive forms [1-3]. Recent studies suggest that heterozygous COL4A3 or COL4A4 mutations may be more prevalent in patients previously diagnosed with isolated thin basement membrane nephropathy, familial hematuria, or even presumed primary IgAN [4,7]. Such overlapping findings can make it challenging to distinguish between isolated IgAN and coexisting hereditary nephropathies purely based on biopsy findings, especially when classic Alport features, such as GBM lamellation, are absent [2,4].

In our case, the absence of lamellation or splitting of the GBM on electron microscopy initially argued against a diagnosis of Alport syndrome. However, genetic testing provided critical diagnostic clarity, identifying a pathogenic COL4A3 mutation and a likely pathogenic COL4A4 variant, supporting autosomal dominant Alport syndrome [4]. This highlights the increasing role of genetic testing in the differential diagnosis of glomerular diseases presenting with hematuria and proteinuria.

The management of IgAN is evolving, with therapies such as SGLT2 inhibitors and endothelin receptor antagonists like sparsentan showing promise in reducing proteinuria and slowing disease progression [8,9]. However, the presence of coexisting Alport syndrome complicates treatment decisions, as some interventions may be less effective in hereditary basement membrane disorders [2]. Furthermore, the high costs of newer therapies pose significant challenges for patients without robust insurance coverage, as was the case with our patient [5,6]. Efforts to secure patient assistance programs are crucial to ensuring equitable access to emerging treatments.

Although our patient’s proteinuria was assessed using standard clinical laboratory methods, it is noteworthy that advanced techniques like high-performance gel-permeation chromatography can provide highly detailed analysis of urinary proteins [10,11]. Nonetheless, such methods are not commonly used in routine clinical practice due to their complexity and cost.

Our case underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach, combining nephrology, pathology, genetics, and even urology, given our patient’s concomitant urological findings. Ultimately, recognition of dual pathology is essential for accurate prognosis, genetic counseling, and optimal treatment planning.

Dual nephropathies, such as IgA nephropathy and autosomal dominant Alport syndrome, require a high index of clinical suspicion and the use of genetic testing for accurate diagnosis. Financial barriers can significantly impact management decisions, but proactive measures, including enrollment in assistance programs, are crucial to bridge these gaps. Additionally, genetic counseling should be offered to patients with COL4A3 or COL4A4 mutations to inform family members about potential risks and inheritance patterns.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication. Institutional review board approval was not required for a single-patient case report.

- Guo Y, Liu X, Yang H. Tale of two nephropathies: co-occurring Alport syndrome and IgA nephropathy. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22:79.

- Kashtan CE. Alport syndrome: an inherited disorder of renal, ocular, and cochlear basement membranes. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(3):627-642. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005792-199909000-00005

- Savige J, Ariani F, Mari F, Kashtan C, Ding J, Flinter F. Expert guidelines for the management of Alport syndrome and thin basement membrane nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(3):364–375. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2012020148

- Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, Cetincelik U, Homstad A, Alonso AS, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253-1259. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2014.305

- Polanco N, Praga M. Socioeconomic aspects of IgA nephropathy management. Kidney Int Suppl. 2020;10(2):S100-S109.

- Tan J, Lee R, Kim S. Socioeconomic disparities in treatment access among patients with glomerular disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78(2):205–215.

- Gast C, Pengelly RJ, Lyon M, Bunyan DJ, Seaby EG, Graham N, et al. Collagen (COL4A) mutations and their possible role in thin basement membrane nephropathy and IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(8):1321–1331. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfv325

- Lafayette RA, Rovin BH. Filspari (sparsentan) for IgA nephropathy: a new era in treatment. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):477-479.

- Barratt J, Lafayette RA, Kristensen J. Sparsentan vs irbesartan in patients with IgA nephropathy (PROTECT): interim analysis of a randomized, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10383):1953-1963.

- Hayakawa K, Terentyeva EA, Tanae A, De Felice C, Tanaka T, Yoshikawa K, Yamauchi K. Urinary protein and albumin determinations by high-performance gel-permeation chromatography. J Liquid Chromatogr. 1995;18:3955-3968. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10826079508013738

- Terentyeva EA, Hayakawa K, Tanae A, Katsumata N, Tanaka T, Hibi I. Urinary biotinidase and alanine excretion in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1997;35:21-24. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.1997.35.1.21