More Information

Submitted: January 07, 2026 | Accepted: January 29, 2026 | Published: January 30, 2026

Citation: Pourmahdigholi F. Resistance Training Improves Fluid Imbalance Symptoms in Hemodialysis Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clini Nephrol. 2026; 10(1): 008-015. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jcn.1001170

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jcn.1001170

Copyright license: © 2026 Pourmahdigholi F. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Resistance training; Hemodialysis; Fluid imbalance; Dyspnea; Muscle cramps; Randomized controlled trial

Resistance Training Improves Fluid Imbalance Symptoms in Hemodialysis Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Fatemeh Pourmahdigholi*

Department of Sport Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Taleghani Hospital Research Development Committee, Tehran, Iran

*Corresponding author: Fatemeh Pourmahdigholi, Department of Sport Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Taleghani Hospital Research Development Committee, Tehran, Iran, Email: [email protected]

Introduction: Fluid imbalance contributes to symptoms such as intradialytic hypotension, muscle cramps, and dyspnea in hemodialysis patients. Exercise therapy may reduce these symptoms, but data on structured resistance training remain limited. This randomized controlled trial evaluated the effect of resistance training on fluid imbalance–related symptoms.

Materials and Methods: Twenty-six adult hemodialysis patients were randomized 1:1 to either resistance training plus lifestyle advice or lifestyle advice alone. The intervention consisted of 20-minute resistance training sessions performed three times weekly for 20 weeks. Outcomes included intradialytic muscle cramps, exertional dyspnea (NYHA class), intradialytic dyspnea (Borg scale), and body composition variables. Linear mixed-effects models were used to assess changes over time. Ethical approval was obtained (IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1402.531). All participants provided written informed consent.

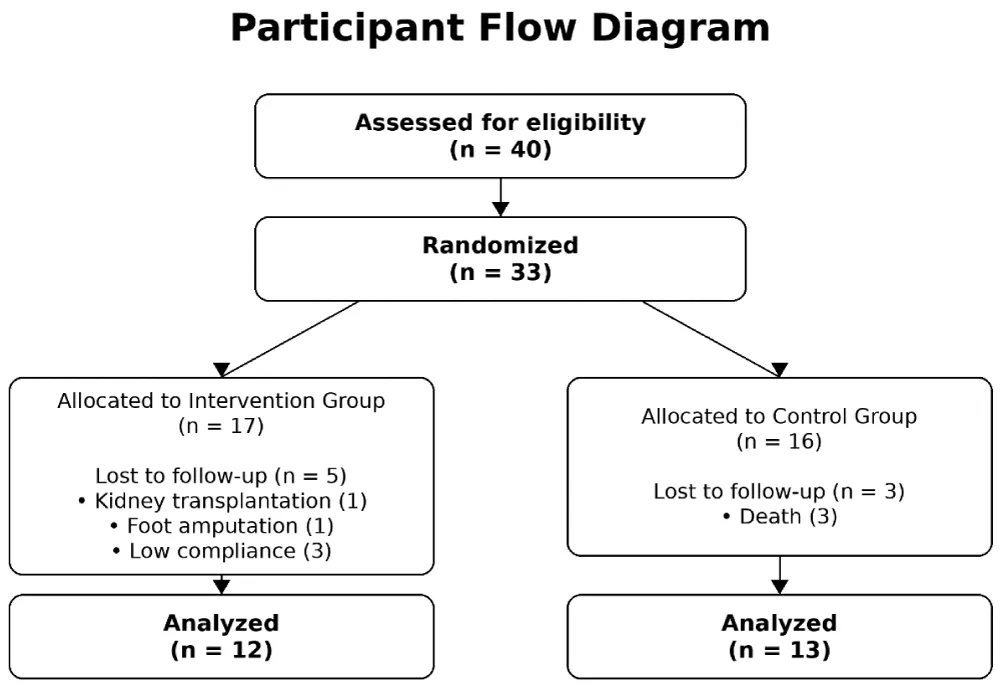

CONSORT checklist completed; CONSORT flow diagram referenced.

Results: Twenty-six participants completed the study. The intervention group experienced significant reductions in muscle cramps (β = −1.993, p = 0.024), exertional dyspnea (β = −1.443, p = 0.019), and intradialytic dyspnea (β = −2.275, p < 0.001). No significant changes were observed in skeletal muscle mass or total body water. No major adverse events occurred.

Discussion: Resistance training effectively improved fluid imbalance–related symptoms and was safe and feasible among hemodialysis patients. These findings support incorporating resistance training into dialysis care to improve symptom burden and clinical tolerance.

Background

Chronic kidney disease affects approximately 10% of the global population and continues to rise, with millions of patients requiring long-term maintenance hemodialysis worldwide [1,2]. Despite improvements in dialysis delivery, dialysis-related symptom burden remains substantial and continues to impair quality of life, physical function, and clinical outcomes [3,4].

Poor fluid balance control and dialysis inadequacy are strongly associated with distressing symptoms such as muscle cramps, dyspnea, hypotension, restless leg syndrome, sleep disturbances, and hemodynamic instability [5-7]. Reduced physical function, poor conditioning, and malnutrition further worsen patients’ medical and psychological status [6]. These challenges have led to the development of lifestyle modification strategies collectively referred to as renal rehabilitation, incorporating nutritional counseling and structured exercise programs [8,9].

Recent evidence supports both intradialytic and interdialytic exercise as effective interventions to improve dialysis tolerance, reduce symptom burden, and enhance quality of life [10,11]. Even low-intensity exercise has been shown to improve physical performance and functional capacity in hemodialysis patients [12,13]. Importantly, exercise is considered a safe non-pharmacological intervention and does not increase routine adverse events when appropriately supervised [14,15]. Advances in exercise prescription now include resistance training, combined modalities, interval training, virtual reality–based exercise, and structured programs such as Tai Chi and yoga [16,17].

Objective

Resistance training has demonstrated benefits in improving quality of life, depressive symptoms, aerobic capacity, muscle strength, muscle wasting, and hemodynamic control in patients undergoing hemodialysis [6,18]. Promising effects on sarcopenia and related biomarkers have also been reported [19,20]. However, evidence regarding its impact on dialysis-related symptoms associated with fluid imbalance remains limited [21].

Resistance training protocols vary widely in intensity, progression, timing, and equipment, and patient-related factors may influence outcomes [22]. A well-designed, feasible protocol that promotes patient adherence and yields clinically meaningful benefits may contribute to future guideline development [23]. Given that aerobic exercise alone may not consistently improve dialysis-related outcomes compared with usual care [9,24], this study aimed to evaluate the effect of adding a structured resistance training program to routine lifestyle advice on fluid imbalance–related symptoms in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis.

Study design

Patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis in a single hemodialysis center were enrolled in the study based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria included patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis for at least 3 months before entering the study, aged 18 to 75 years, with the ability to walk without assistance, and with stable hemodynamic and blood sugar status.

The exclusion criteria included kidney transplantation, pregnancy, any serious illness, including mental disorders and malignant diseases, instability of medical condition, including hospitalization and hemodynamic changes resistant to treatment.

After being introduced to a specialized sports medicine assistant, these patients were re-examined for musculoskeletal health and ability to perform exercises. Finally, 33 of these patients were included in the study, and all underwent initial assessments and general lifestyle recommendations, including the appropriate amount of weekly aerobic, strength, and balance exercises, and appropriate nutritional recommendations, including the required amount of protein intake and proper nutrition in terms of proper water and electrolyte intake. Then, the patients were interviewed for background information, including age, gender, height, weight, dialysis history, number of dialysis sessions, presence of comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease), degree of dyspnea on exertion, severity of dyspnea during dialysis, and severity of muscle cramps. The weight and blood pressure of the subjects were recorded before and after dialysis. Bioimpedance testing was performed on the patients with the Inbody S10 device 30 minutes after the end of dialysis in a lying position, and a 6-minute walking test was performed on the patients.

Setting and participants

The study population was patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis at the Dialysis Center of Imam Hussein Hospital (Tehran, Iran). Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 40 people were initially selected and entered into the study (to predict possible drops) by the head nurse of the dialysis department under the supervision of the head of the department (nephrology specialist).

Patients were randomly divided into two groups using simple randomization based on a numbered table by the head nurse; 17 patients were in the intervention group, and 16 patients were in the control group. The control group was repeatedly and regularly visited and received lifestyle modification advice, but did not receive a structured exercise program.

Of the 33 confirmed patients, 3 patients in the control group were excluded from the study due to death, 1 patient in the intervention group due to kidney transplantation, 1 patient due to foot amputation and 3 patients due to lack of proper cooperation, and finally 26 patients, including 13 patients in the intervention group and 12 patients in the control group, completed the intervention.

Participant Flow Diagram.

Randomization and blinding

Eligible hemodialysis patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the intervention or control group using a computer-generated randomization sequence. Due to the nature of the intervention, participants and exercise supervisors could not be blinded to group assignment; however, outcome assessors and data analysts were blinded to group allocation to minimize bias in the evaluation of both primary and secondary outcomes.

Intervention

In addition to general and common recommendations, the intervention group received a regular program of strength training. This program was performed three sessions per week for 20 minutes. Initially, for 4 weeks, the exercises were performed under full supervision before each dialysis session in the dialysis center, and gradually, after the first month, the exercises were performed at home and on days other than dialysis. During this period, the patients were regularly examined and interviewed face-to-face and directly in terms of proper performance of the exercises and progress of the exercises, including increasing the number of sets and adding more exercises if possible. And given the continuous presence of a sports medicine assistant in the dialysis center, the level of cooperation and attention of the patients to the exercises was assessed verbally. All of this supervision was carried out by a sports medicine assistant in collaboration with experienced dialysis center staff.

Each exercise session included: 5 to 10 minutes of warm-up in the form of walking or active stretching movements. The main body of the exercises included resistance exercises aimed at increasing muscle endurance specific to large upper body muscle groups. The lower body and the central body were performed. Due to the lack of suitable conditions for performing the maximum muscle power test or its multiples for all muscle groups. The percent of reserve heart rate wasn’t reliable due to different medication consumptions. The intensity of the exercises was determined as low to moderate intensity by RPE (rating of perceived exertion) = 11-14 on the BORG SCALE 6-20, and the elastic band exercises were adjusted according to the ability of each individual. Due to the low ability of the individuals, yellow or green elastic bands were usually suitable for them. According to the ability of each individual, the number of sets started from the set length to create initial readiness, and the number of sets was gradually increased. The number of repetitions of each movement was 10 repetitions, which were performed as 1 second concentric phase, a 2-second isometric phase, and 2 seconds eccentric phase to prevent muscle cramps and damage. After each movement, a corresponding stretching was performed for 15 seconds.

Resistance exercises included: (All exercises except core exercises were performed with elastic bands).

- Strengthening the anterior compartment of the arm (biceps curl)

- Strengthening the shoulder lifting compartment, including the upper trapezius muscle (shoulder shrug)

- Strengthening the deltoid muscle (forward flexion and abduction of the shoulder)

- Strengthening the anterior compartment of the thigh, including the quadriceps muscle (leg curl)

- Strengthening the thigh abductor muscles, including the gluteus medius and tensor fascia Lata (hip abduction)

- Strengthening the posterior thigh muscles, including the gluteus maximus and hamstrings (hip extension)

- Strengthening the core muscles (dead bug and double leg bridge)

Then the cool-down phase was performed for 5 minutes again with active stretching and walking.

The exercises progressed gradually by increasing the number of sets up to 3 sets and adding exercises, including wall squats, walking lunges, heel raises, and simple balance exercises (double and single leg and tandem stance with eyes opened and closed). The exercises and their progress were monitored by a specialized sports medicine assistant. A written informed consent form was signed by all patients. Necessary advice was given on possible complications.

Primary outcomes

Blood pressure changes during dialysis: Blood pressure changes during dialysis were measured by direct measurement at the beginning and last minutes of the hemodialysis session or when the patient had symptoms of intradialytic hypotension (IDH) by a calibrated dial pressure gauge manometer (in mmhg) by trained staff, and the systolic and diastolic blood pressure and the differences were recorded precisely at the week 0,12,20.

Muscle cramps during dialysis: The severity of muscle cramps (calf muscles) during the hemodialysis session was measured by severity score from 1-3 (one being the least severe and three being the most severe). These were recorded directly through interviews and by completing a written Questionnaire.

Edema

Weight differences before and after dialysis: Weight differences before and after dialysis sessions were measured using a calibrated digital scale, and the differences were recorded in kilograms in weeks 0, 12, and 20.

Dyspnea on exertion: Exertional dyspnea was assessed by New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification 1-4 (Class I: No limitations. Ordinary physical activity does not cause undue fatigue, dyspnea, or palpitations. Mets>7 Class II Slight limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea, or angina pectoris. Mets>5 Class III Marked limitation of physical activity. Less than ordinary physical activity leads to symptoms, Mets = 2–3, Class IV, Unable to carry on any physical activity without discomfort Mets<1.6), it was recorded directly with an oral questionnaire in week 0 and 20.

Dyspnea during dialysis: Dyspnea during dialysis sessions was measured by the Borg dyspnea scale 1-5 (1 stands for the least severe dyspnea and 5 for the most severe dyspnea). It was recorded directly by questionnaire filling in weeks 0, 12, and 20.

Secondary outcomes

Body composition: Body composition was measured indirectly with InBody S10, which has over 0.0984 percent similarity with DEXA assessment based on recent reliability studies and is designed specifically for bedridden or disabled patients. SMM (skeletal muscle mass), PBF (percent body fat), and TBW (total body water) were recorded with the patient in a lying position, 30 minutes to the end of the dialysis session, with a calibrated system and standard ports in standard position to best evaluate “Dry weight”. The test was recorded at 0 and 20 weeks.

Aerobic capacity

Aerobic capacity and physical function were tested through the 6-minute walk test(6MWT), which is validated for patients with poor medical and physical condition like hemodialysis patients. The test was performed in a 20-meter space, and trained staff supervised the test with standard instructions in weeks 0 and 20.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was determined a priori to ensure adequate power for detecting a clinically meaningful group × time interaction in the longitudinal analysis. Assuming a two-sided significance level of 0.05, a power of 80%, and a conservative estimate of variability, a minimum of 16 participants per group was required. To account for an anticipated attrition rate of 15%, the sample size was increased to 19 participants per group, resulting in a total required sample of 38 participants to ensure sufficient statistical power for detecting meaningful differences between the intervention and control groups over time.

Statistical analysis

Given the longitudinal nature of the study data, one of the main challenges was handling missing values. To address this issue, multiple imputation (MI) methods were applied. Three approaches were used: predictive mean matching (PMM), random forest (RF), and weighted predictive mean matching (WPMM). For each method, five datasets with 10 iterations were generated, and these were subsequently combined into a single final imputed dataset.

To evaluate the performance of the imputation methods, diagnostic plots as well as summary indices including mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage of the data before and after imputation were examined. Based on these results, WPMM was identified as the most appropriate method, and all imputed data in the present study were prepared accordingly.

Line plots were drawn to compare the trajectories of variables between the intervention and control groups over time, allowing assessment of overall trends. To analyze the effect of the intervention on the variables of interest, a linear mixed-effects model (LMM) was fitted. This model accounted for both individual-level differences and within-subject changes over time, providing a suitable error structure. The error structure was specified as unstructured, and estimation was performed using the REML approach to maximize the log-likelihood. Finally, the LMM was fitted to assess the longitudinal intervention effects.

All statistical analyses were conducted using RStudio version 2024.12.0+467. For multiple imputation, the packages mice, missForest, missMDA, and Amelia were utilized. Line plots were generated with ggplot2 and dplyr. For fitting the linear mixed-effects models, the packages nlme, lme4, and ordinal were applied. Statistical significance was assessed at a 95% confidence level.

Interpretive charts for the variables Cramps, NYHA, and Dyspnea showed that the probability of individuals being in more severe categories of these symptoms was much lower in the intervention group than in the control group. These charts indicate that PBF had a lower mean in the intervention group at both time points compared to the control group, while SMM and TBW had higher means in the intervention group at both time points compared to the control group. Table 1 results showed that in the control group, 7 patients (43.8%) were female and 9 patients (56.3%) were male, while in the intervention group, 5 patients (29.4%) were female and 12 patients (70.6%) were male. This statistic shows that the number of male patients was higher than the number of female patients in both groups. However, the chi-square test (p - value = 0.392) indicated that there was no significant difference in the distribution of gender between the two groups. The mean age of patients in the control group was 61.31 years (standard deviation 12.99), and in the intervention group was 55.59 years (standard deviation 13.95). Although the mean age difference between the two groups was about 5 years, the independent t-test (p - value = 0.233) showed that this difference was not statistically significant. Therefore, it can be said that the age of patients in both groups was similar. The mean weight of patients in the control group was 78.25 kg (standard deviation 16.65), and in the intervention group was 72.35 kg (standard deviation 15.40). Although the mean weight was higher in the control group, the independent t-test (p - value = 0.299) showed that this difference was not significant. Also, the mean height of patients in the control group was 167.06 cm (standard deviation 9.26), and in the intervention group was 168.18 cm (standard deviation 11.98). This difference was also not significant, with a p - value of 0.758. The mean body mass index (BMI) in the control group was 28.13 (standard deviation 5.98) and in the intervention group was 25.42 (standard deviation 4.09). Although BMI was higher in the control group, the independent t-test (p - value = 0.138) indicated that this difference was not significant. The mean dialysis days per week in the control group was 3.31 days (standard deviation 0.47), and in the intervention group was 3.35 days (standard deviation 0.78), and this small difference was also not significant with a p - value of 0.861. The mean total body water (TBW) in the control group was 38.07 liters (standard deviation 7.55), and in the intervention group was 38.93 liters (standard deviation 9.00). The independent t-test (p - value = 0.805) showed that this difference was also not significant. The mean body fat percentage (PBF) in the control group was 27.50% (standard deviation 6.28) and in the intervention group was 29.15% (standard deviation 7.14), which, with a p - value of 0.557, was also not statistically significant. Finally, the mean skeletal muscle mass (SMM) in the control group was 30.99 kg (standard deviation 10.92) and in the intervention group was 22.70 kg (standard deviation 7.59). This was the only variable that showed a significant difference between the two groups (p - value = 0.040). In other words, the control group had higher skeletal muscle mass compared to the intervention group, which may indicate different therapeutic effects. Overall results showed that in most of the examined variables, no significant differences were observed between the two groups. The only significant difference was reported in skeletal muscle mass (SMM), which can help better understand patient characteristics and the effects of therapeutic interventions.

| Discussion: General characteristics of patients at baseline. | |||

| Variables | Control | Intervention | p - value |

| Gender (Female) | 7 (43.8) | 5 (29.4) | 0.392 |

| Gender (Male) | 9 (56.3) | 12 (70.6) | |

| Age | 61.31 (12.99) | 55.59 (13.95) | 0.233 |

| Weight | 78.25 (16.65) | 72.35 (15.40) | 0.299 |

| Height | 167.06 (9.26) | 168.18 (11.98) | 0.758 |

| BMI | 28.13 (5.98) | 25.42 (4.09) | 0.138 |

| Dialysis days/week | 3.31 (0.47) | 3.35 (0.78) | 0.861 |

| TBW | 38.07 (7.55) | 38.93 (9.00) | 0.805 |

| PBF | 27.50 (6.28) | 29.15 (7.14) | 0.557 |

| SMM | 30.99 (10.92) | 22.70 (7.59) | 0.040* |

The different variables, including muscle cramps (Cramps), exertional dyspnea (NYHA), dyspnea during dialysis (Dyspnea), total body water changes (TBW), body fat percentage (PBF), and skeletal muscle mass (SMM), were analyzed. For muscle cramps, the group β was 0.160 with a p - value of 0.918, indicating no significant difference at baseline. The effect of time (β = -0.242, p = 0.529) was also not significant. However, the time × group interaction (β = -1.993, p = 0.024) was significant, indicating that the odds of more severe muscle cramps in the intervention group compared to the control group decreased by 1.99 times over time, and this reduction was statistically significant.

For exertional dyspnea (NYHA), the group β was -2.444 with a p - value of 0.271, indicating no significant difference at baseline. The effect of time (β = 0.094, p = 0.916) was not significant. The time × group interaction (β = -1.443, p = 0.019) was significant, indicating a statistically significant 1.443-fold reduction in the odds of more severe dyspnea in the intervention group over time.

For dyspnea during dialysis, the group β was 0.994 with a p - value of 0.515, indicating no significant difference at baseline. The effect of time (β = -0.008, p = 0.981) was not significant. However, the time × group interaction (β = -2.275, p < 0.001) was significant, showing that the odds of more severe dyspnea in the intervention group compared to the control group decreased by 2.27 times over time, which was statistically significant.

Regarding total body water (TBW), the group β was -1.008 (p = 0.836), and the time effect (β = -2.212, p = 0.273) was not significant. The time × group interaction (β = 1.836, p = 0.511) was also not significant.

For body fat percentage (PBF), the group β was -1.268 (p = 0.808), indicating no significant difference at baseline. The effect of time (β = 5.606, p = 0.011) was significant, suggesting that changes over time had a positive effect on body fat percentage in the intervention group. However, the time × group interaction (β = -2.529, p = 0.393) was not significant.

Finally, for skeletal muscle mass (SMM), the group β was 2.744 (p = 0.465), showing no significant difference at baseline. The effect of time (β = -1.225, p = 0.427) and the time × group interaction (β = -0.157, p = 0.941) were also not significant (Table 2).

| Table 2: Results of fitting the linear mixed-effects model over time between intervention and control groups. | |||

| Variables | β | St. Error | p - value |

| Cramps - Group | 0.160 | 1.566 | 0.918 |

| Cramps - Time | -0.242 | 0.358 | 0.529 |

| Cramps - Time*Group | -1.993 | 0.583 | 0.024* |

| NYHA - Group | -2.444 | 2.221 | 0.271 |

| NYHA - Time | 0.094 | 0.891 | 0.916 |

| NYHA - Time*Group | -1.443 | 1.234 | 0.019* |

| Dyspnea - Group | 0.994 | 1.530 | 0.515 |

| Dyspnea - Time | -0.008 | 0.364 | 0.981 |

| Dyspnea - Time*Group | -2.275 | 0.676 | <0.001* |

| TBW - Group | -1.008 | 4.83 | 0.836 |

| TBW - Time | -2.212 | 1.98 | 0.273 |

| TBW - Time*Group | 1.836 | 2.76 | 0.511 |

| PBF - Group | -1.268 | 5.179 | 0.808 |

| PBF - Time | 5.606 | 2.099 | 0.011* |

| PBF - Time*Group | -2.529 | 2.924 | 0.393 |

| SMM - Group | 2.744 | 3.71 | 0.465 |

| SMM - Time | -1.225 | 1.52 | 0.427 |

| SMM - Time*Group | -0.157 | 2.12 | 0.941 |

β: For the variables Cramps, NYHA, and Dyspnea, β is interpreted as the odds of being in higher severity categories. For TBW, PBF, and SMM, β is interpreted as the increase in the mean value of the variable in the intervention group compared to the control group.

Principal findings

This study introduced a resistance training protocol that was well-designed, well-supervised, and well-tolerated. It was as easy as performed by poorly conditioned patients. Patients faced no more adverse effects than the control group. Hospitalization during the intervention interval didn’t significantly differ between groups. Exercise-related adverse events were a single case of AV Fistula thrombophlebitis in his left hand despite careful supervision and advising to perform low-intensity exercise with the affected extremity.

Findings showed significant improvements in symptoms related to volume changes before and during dialysis sessions. Weight differences, which were directly related to pre-dialysis edema was improved significantly among the intervention group in comparison to the control group. Blood pressure changes and muscle cramps, which reflect volume changes during dialysis related to pre-dialysis overload and imbalance, were markedly improved as well. Exertional dyspnea, which is firstly because of cardiovascular impairments and secondly related to volume overload resulting in pulmonary edema, was improved, and patients faced less severe dyspnea during dialysis sessions. Patients in the intervention group preserved their muscle mass and had higher dry weight and lower body fat. Total body water couldn’t be assessed with the post-dialysis bioimpedance protocol, and 6MWT results didn’t t show significant improvements after the intervention.

Comparison with existing literature

Intra dialytic hypotension is the end result of a multifactorial cycle of volume overload , ultrafiltration rate and cardiovascular condition(cardiac output ,arterial and autonomic problems) [3,7,25] lower BP (specially DBP) and higher blood pressure changes are strongly associated with lower physical function [4,26] As our study resulted the effect of resistance training in controlling blood pressure changes during hemodialysis session different studies have shown the effect of intradialytic aerobic ,anaerobic (interval or continuous) [27] and resistance training in preventing intradialytic hypotension and considering it as a non-medical intervention in stabilizing hemodynamics [6,28,29] other studies have shown hemodynamic stabilizing effects in day -time [30,31] as intradialytic resistance or aerobic training is feasible and well-tolerated with patients and seems to be better supervised but it has intensity and progression limitations and benefits are limited as well [32]. So a better design might help to reach much more benefits of exercise. Dialysis-related symptoms (like muscle cramps) are strongly predicted by physical function levels [33]. Improvements in dialysis adequacy and reducing intradialytic symptoms (like muscle cramps. Restless leg syndrome, fatigue and sleep disorders) [5] by exercise interventions besides other conservative treatments [34,35] have been confirmed in this study and same studies before but most studies had an intradialytic aerobic exercise approach [36] some other studies assessed the effectiveness of non-exercise interventions(like pneumatic compression) to improve patient compliance but they didn’t t reach the significant changes in controlling fluid changes and related symptoms as exercise reached [37]. Aerobic capacity and other cardiopulmonary factors changes due to exercise have been concluded in many previous studies using different methods [38] (CPET cardiopulmonary exercise tests, maximal and submaximal tests and field tests like 6MWT) but this study underpowered to determine the impact of resistance training on aerobic capacity. Cardiovascular metabolic biomarkers showed improvements in response to acute and chronic exercise [39-41]. In other studies, evidence is lacking to confirm intra- or extradialytic exercise effects on structural or functional cardiovascular changes [42]. Changes in left ventricular function were not assessed in this study because of low patient compliance with scheduled echocardiography with an echo-fellow cardiology specialist. Body composition changes, muscle and protein-energy wasting prevention has been shown in different studies with nutritional and exercise interventions [43] studies have introduced bioimpedance as a valuable device for assessing body composition in these patients [44,45]. Studies often showed increase in skeletal muscle mass [46] and its effects on lean body mass and body fat were different [47] but intradialytic exercise had limited affect on body composition indexes [1,48,49]. This study showed that the intervention group could preserve muscle mass more than the intervention group [50-55].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include randomized design, supervised intervention, and comprehensive symptom assessment. Limitations include small sample size, potential dietary variability, and limited ability to assess cardiovascular structural changes.

This study demonstrates that a well-designed and supervised resistance training program is a safe and effective adjunctive strategy for improving fluid imbalance–related symptoms in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Incorporating structured resistance training into routine dialysis care may enhance symptom control, treatment tolerance, and overall patient well-being.

Declarations

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of [Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences] (Approval No: [IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1402.531]), and all participants provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Trial registration: The trial was registered at [Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials] with the identifier IRCT20230503058061N2

The authors thank all patients who participated in this study and the staff of [Imam Hossein Hemodialysis Center] for their support during the intervention.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Hattori M, Saito H, Ito Y, Matsumoto K, Takahashi H. Health-related quality of life and symptom prevalence in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37:2301–2309.

- Bello AK, Okpechi IG, Osman MA, Cho Y, Htay H, Jha V. Global epidemiology of chronic kidney disease and dialysis outcomes. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11:e184–e194.

- Usui N, Nakata J, Uehata A, Ando S, Saitoh M, Kojima S, et al. Association of cardiac autonomic neuropathy assessed by heart rate response during exercise with intradialytic hypotension and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2022;101(5):1054–1062. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2022.01.032

- Hattori K, Sakaguchi Y, Kajimoto S, Asahina Y, Doi Y, Oka T, et al. Intradialytic hypotension and objectively measured physical activity among patients on hemodialysis. J Nephrol. 2022;35(5):1409–1418. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-021-01222-8

- Hargrove N, El Tobgy N, Zhou O, Pinder M, Plant B, Askin N, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on dialysis-related symptoms in individuals undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(4):560–574. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.15080920

- Rhee SY, Song JK, Hong SC, Choi JW, Jeon HJ, Shin DH, et al. Intradialytic exercise improves physical function and reduces intradialytic hypotension and depression in hemodialysis patients. Korean J Intern Med. 2019;34(3):588–598. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2017.020

- Kanbay M, Ertuglu LA, Afsar B, Ozdogan E, Siriopol D, Covic A, et al. An update review of intradialytic hypotension: concept, risk factors, clinical implications and management. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13(6):981–993. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfaa078

- Hoshino J. Renal rehabilitation: exercise intervention and nutritional support in dialysis patients. Nutrients. 2021;13(5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051444

- Uchiyama K, Washida N, Morimoto K, Muraoka K, Kasai T, Yamaki K, et al. Home-based aerobic exercise and resistance training in peritoneal dialysis patients: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2632. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39074-9

- Huang M, Lv A, Wang J, Xu N, Ma G, Zhai Z, et al. Exercise training and outcomes in hemodialysis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Nephrol. 2019;50(4):240–254. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000502447

- Zhao J, Qi Q, Xu S, Shi D. Combined aerobic resistance exercise improves dialysis adequacy and quality of life in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol. 2020;93(6):275–282. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5414/cn110033

- Manfredini F, Mallamaci F, D'Arrigo G, Baggetta R, Bolignano D, Torino C, et al. Exercise in patients on dialysis: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(4):1259–1268. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2016030378

- Yabe H, Kono K, Yamaguchi T, Ishikawa Y, Yamaguchi Y, Azekura H. Effects of intradialytic exercise for advanced-age patients undergoing hemodialysis: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0257918. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257918

- Anding-Rost K, von Gersdorff G, von Korn P, Ihorst G, Josef A, Kaufmann M, et al. Exercise during hemodialysis in patients with chronic kidney failure. NEJM Evid. 2023;2(9):EVIDoa2300057. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/evidoa2300057

- Tarca B, Jesudason S, Bennett PN, Kasai D, Wycherley TP, Ferrar KE. Exercise or physical activity-related adverse events in people receiving peritoneal dialysis: a systematic review. Perit Dial Int. 2022;42(5):447–459. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/08968608221094423

- Turoń-Skrzypińska A, Tomska N, Mosiejczuk H, Rył A, Szylińska A, Marchelek-Myśliwiec M, et al. Impact of virtual reality exercises on anxiety and depression in hemodialysis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):12435. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39709-y

- Wilkinson TJ, McAdams-DeMarco M, Bennett PN, Wilund K. Advances in exercise therapy in predialysis chronic kidney disease, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2020;29(5):471–479. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/mnh.0000000000000627

- Perez-Dominguez B, Suso-Marti L, Dominguez-Navarro F, Perpiña-Martinez S, Calatayud J, Casaña J. Effects of resistance training on patients with end-stage renal disease: an umbrella review with meta-analysis of the pooled findings. J Nephrol. 2023;36(7):1805–1839. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-023-01635-7

- Gadelha AB, Cesari M, Corrêa HL, Neves RVP, Sousa CV, Deus LA, et al. Effects of pre-dialysis resistance training on sarcopenia, inflammatory profile, and anemia biomarkers in older community-dwelling patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021;53(10):2137–2147. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-021-02799-6

- Noor H, Reid J, Slee A. Resistance exercise and nutritional interventions for augmenting sarcopenia outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a narrative review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12(6):1621–1640. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12791

- Bessa B, de Oliveira Leal V, Moraes C, Barboza J, Fouque D, Mafra D. Resistance training in hemodialysis patients: a review. Rehabil Nurs. 2015;40(2):111–126. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/rnj.146

- Zelko A, Rosenberger J, Kolarcik P, Madarasova Geckova A, van Dijk JP, Reijneveld SA. Age and sex differences in the effectiveness of intradialytic resistance training on muscle function. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):3491. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30621-z

- Lambert K, Lightfoot CJ, Jegatheesan DK, Gabrys I, Bennett PN. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for people receiving dialysis: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0267290. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267290

- Greenwood SA, Koufaki P, Macdonald JH, Bulley C, Bhandari S, Burton JO, et al. Exercise programme to improve quality of life for patients with end-stage kidney disease receiving haemodialysis: the PEDAL RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(40):1–52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3310/hta25400

- Fotbolcu H, Oduncu V, Gürel E, Cevik C, Erkol A, Özden K, et al. No harmful effect of dialysis-induced hypotension on the myocardium in patients who have a normal ejection fraction and a negative exercise test. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2012;35(6):671–677. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000342755

- Rodríguez-Chagolla J, Cartas-Rosado R, Lerma C, Infante-Vázquez O, Martínez-Memije R, Becerra-Luna B, et al. Low-intensity intradialytic exercise attenuates the relative blood volume drop due to intravascular volume loss during hemodiafiltration. Blood Purif. 2021;50(2):180–187. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000509273

- Usui N, Nakata J, Uehata A, Kojima S, Saitoh M, Chiba Y, et al. Comparison of intradialytic continuous and interval training on hemodynamics and dialysis adequacy: a crossover randomized controlled trial. Nephrology (Carlton). 2024;29(4):214–221. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.14255

- McGuire S, Horton EJ, Renshaw D, Jimenez A, Krishnan N, McGregor G. Hemodynamic instability during dialysis: the potential role of intradialytic exercise. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:8276912. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8276912

- Chae TS, Kim DS, Ko MH, Won YH. Effect of pre- and post-dialysis exercise on functional capacity using portable ergometer in chronic kidney disease patients. Ann Rehabil Med. 2024;48(4):239–248. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.240005

- Kim JS, Yi JH, Shin J, Kim YS, Han SW. Effect of acute intradialytic aerobic and resistance exercise on one-day blood pressure in patients undergoing hemodialysis: a pilot study. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2019;59(8):1413–1419. Available from: https://doi.org/10.23736/s0022-4707.18.07921-5

- Headley S, Germain M, Wood R, Joubert J, Milch C, Evans E, et al. Blood pressure response to acute and chronic exercise in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton). 2017;22(1):72–78. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.12730

- Ribeiro HS, Cunha VA, Dourado G, Duarte MP, Almeida LS, Baião VM, et al. Implementing a resistance training programme for patients on short daily haemodialysis: a feasibility study. J Ren Care. 2023;49(2):125–133. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jorc.12423

- Kot G, Wróbel A, Kuna K, Makówka A, Nowicki M. The effect of muscle cramps during hemodialysis on quality of life and habitual physical activity. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60(12). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60122075

- Jahromi LSM, Vejdanpak M, Ghaderpanah R, Sadrian SH, Dabbaghmanesh A, Roshanzamir S, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture on pain severity and frequency of calf cramps in dialysis patients: a randomized clinical trial. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2024;17(2):47–54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.51507/j.jams.2024.17.2.47

- Barros FS, Pinheiro BV, Lucinda LMF, Rezende GF, Segura-Ortí E, Reboredo MM. Exercise training during hemodialysis in Brazil: a national survey. Artif Organs. 2021;45(11):1368–1376. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/aor.14018

- Parsons TL, Toffelmire EB, King-VanVlack CE. The effect of an exercise program during hemodialysis on dialysis efficacy, blood pressure, and quality of life in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients. Clin Nephrol. 2004;61(4):261–274. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5414/cnp61261

- Álvares VRC, Ramos CD, Pereira BJ, Pinto AL, Moysés RMA, Gualano B, et al. Pneumatic compression, but not exercise, can avoid intradialytic hypotension: a randomized trial. Am J Nephrol. 2017;45(5):409–416. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000471513

- Hsiao CC, Chou CY, Fang JT, Chang SC, Liu KC, Huang SC. Cardiopulmonary response to acute exercise before hemodialysis: a pilot study. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2024;49(1):735–744. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000540767

- Isnard-Rouchon M, Coutard C. Exercise as a protective cardiovascular and metabolic factor in end-stage renal disease patients. Nephrol Ther. 2017;13(7):544–549. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nephro.2017.01.027

- Lo CY, Li L, Lo WK, Chan ML, So E, Tang S, et al. Benefits of exercise training in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(6):1011–1018. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6386(98)70076-9

- Goldberg AP, Geltman EM, Gavin JR 3rd, Carney RM, Hagberg JM, Delmez JA, et al. Exercise training reduces coronary risk and effectively rehabilitates hemodialysis patients. Nephron. 1986;42(4):311–316. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000183694

- Grigoriou SS, Giannaki CD, George K, Karatzaferi C, Zigoulis P, Eleftheriadis T, et al. A single bout of hybrid intradialytic exercise did not affect left-ventricular function in exercise-naïve dialysis patients: a randomized, crossover trial. Int Urol Nephrol. 2022;54(1):201–208. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-021-02910-x

- Sabatino A, Regolisti G, Karupaiah T, Sahathevan S, Sadu Singh BK, Khor BH, et al. Protein-energy wasting and nutritional supplementation in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(3):663–671. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.06.007

- Broers NJ, Martens RJ, Cornelis T, Diederen NM, Wabel P, van der Sande FM, et al. Body composition in dialysis patients: a functional assessment of bioimpedance using different prediction models. J Ren Nutr. 2015;25(2):121–128. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2014.08.007

- Koźma-Śmiechowicz MA, Gajewski B, Fortak P, Gajewska K, Nowicki M. Physical activity, body composition, serum myokines and the risk of death in hemodialysis patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(11). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59112020

- Ekramzadeh M, Santoro D, Kopple JD. The effect of nutrition and exercise on body composition, exercise capacity, and physical functioning in advanced CKD patients. Nutrients. 2022;14(10). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102129

- Bakaloudi DR, Siargkas A, Poulia KA, Dounousi E, Chourdakis M. The effect of exercise on nutritional status and body composition in hemodialysis: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2020;12(10). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103071

- Usui Y, Kimura K, Yamagata K. Exercise therapy and intradialytic symptom burden in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15:2047–2055.

- Wilkinson TJ, Clarke AL, Nixon DGD, Watson EL, Smith AC. Symptom burden and physical function in contemporary hemodialysis populations. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8:1180–1189.

- Kanbay M, Ertuglu LA, Afsar B, Ozdogan E, Siriopol D, Covic A. Intradialytic hypotension: updated pathophysiology, risk factors, and management strategies. Clin Kidney J. 2023;16:981–993.

- Kot G, Wróbel A, Kuna K, Makówka A, Nowicki M. Muscle cramps during hemodialysis and their association with quality of life. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60:1923.

- Lambert K, Lightfoot CJ, Jegatheesan DK, Gabrys I, Bennett PN. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for people receiving dialysis: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0267290.

- Anding-Rost K, von Gersdorff G, von Korn P, Ihorst G, Josef A, Kaufmann M. Exercise during hemodialysis in patients with chronic kidney failure: a randomized clinical trial. NEJM Evid. 2023;2:EVIDoa2300021.

- Gomes Neto M, de Lacerda FFR, Lopes AA, Martinez BP. Exercise interventions and intradialytic symptoms in chronic kidney disease: an updated meta-analysis. J Ren Nutr. 2023;33:345–356.

- Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training in adults with chronic kidney disease: recent advances and clinical implications. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18:499–510.